20

06

.22

Connected Kitchen closing blog

The aim of our project was to develop a greater understanding of commercial kitchen behaviours linked to hygiene and health & safety through the development and testing an adaptive and interactive multisensory toolkit – with the potential to interact with cleaning products and devices.

The idea came about from a variety of different projects we had previously worked on and in response to the pandemic, which unearthed challenges for organisations, such as the Food Standards Agency, around health & safety compliance when access to kitchens is unavailable.

Our first blog described our initial user studies which involved developing multi-sensor systems to track and model the behaviour of people in commercial kitchen environments and their attitudes towards hygiene cleaning. How could sensor data be used to help people understand their cleaning behaviours and encourage more effective cleaning? We also considered how data could be used for remote auditing and cleaning and commenced work to develop several interactive cleaning products.

A second blog described further experiments and we released some early findings.

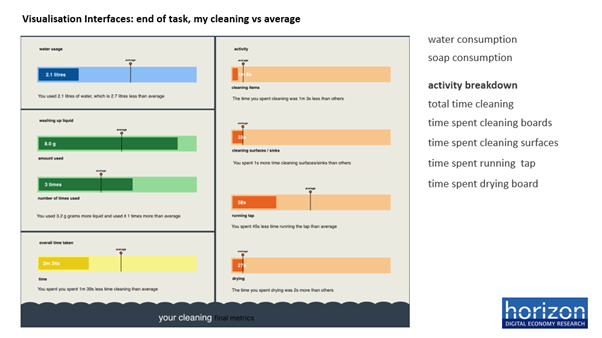

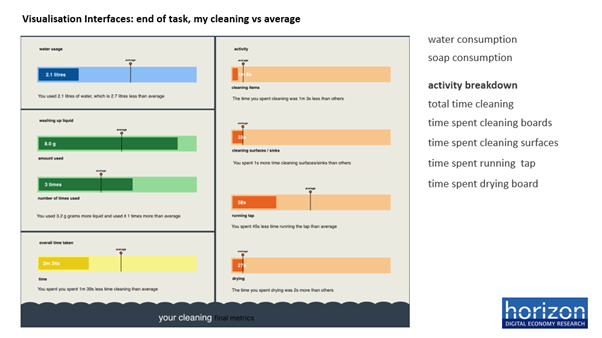

This, our final blog post, describes our final user study. Thirteen participants were invited to conduct a pre-task survey – which involved 8 kitchen food-related and 6 cleaning-related activities, to rank in order of importance. Next, they performed a washing up task which involved cleaning and drying chopping boards and work surfaces, followed by a post task interview – conducted after visual feedback relating to their cleaning activity. The data we provided included details such as time they spent cleaning, pressure applied to the products they cleaned, how much water they used, how well they thought they had done and their trust in the data collected.

So, what did we discover?

In relation to the kitchen food-related questions, participants ranked washing hands after touching pets at the top. Interestingly, a ‘red herring’ question about washing raw poultry was ranked second. Regarding the cleaning-related questions, washing hands was ranked as most important. We also asked participants about their cleaning behaviour. When did they clean their work surfaces and how often they washed their hands? We had a variety of answers ranging from cleaning work surfaces every day to every other day, between 3–4 days and every 2 weeks. Compared to others, all participants felt their cleaning behaviours were ‘cleaner than most’.

Measuring ‘cleanliness’ is a non-trivial task. Early in the project we investigated the use of ATP swabs; an industry standard that measures the amount of adenosphine triphosphate (an energy molecule found in all living things) an indicator of the presence of microorganisms such as bacteria. Unfortunately, we found it difficult to get consistent, repeatable results, so instead prompted for ultraviolet (UV) marking; typically used in hygiene training, where items are marked with an invisible UV dye prior to cleaning and the residue (representing missed areas and cross-contamination) is revealed under a UV lamp at the end. With our early participant studies we recorded users wearing wrist and waist accelerometers, performing a cleaning task, with a UV ‘reveal’ at the end. This work informed our main study, where we deployed a range of sensors to measure, water usage, cleaning activity (using sensors in a sponge handle) and washing-up liquid usage (using a weight-sensor). These sensors were used to both provide real-time feedback to participants during cleaning and post-task feedback to compare their cleaning against others. As with the first study we presented the UV markings, but this time alongside the sensor data.

Most found the UV markers revealing especially after having completed the cleaning task. Many of them commented on their water usage and all trusted the data we showed to them, whilst some concern was expressed about surveillance. We were also interested to learn whether this type of information would be useful and influence participants future cleaning habits. Many of them stated that they would pay particular attention to their water usage.

To address how our research/findings could work in practice and translate into a commercial kitchen environment, we are organised a workshop with behavioural and social scientists form the Food Standards Agency. At the workshop we gave an overview of the sensor technologies and the main findings from our user studies. Participants were interested in the use of the multi-sensors as a way of understanding behaviours, as most kitchen studies only used videos, which have limitations, such as the need for coding specific actions and behaviours. We also discussed the challenges of scaling up the Connected Kitchen study in terms of cost, and concerns about privacy, if used in real world environments. Several participants mentioned that the value proposition of the technology to a business and worker must be clear and had concerns that it might be used for performance monitoring. It was discussed that a kitchen hospital might be a great place to start as they are even more concerned about cleanliness and hygiene than a standard kitchen.

Tags:

adenosphine triphosphate,

ATP swab,

data,

health & safety,

hygiene,

kitchen,

sensor data,

UV marking